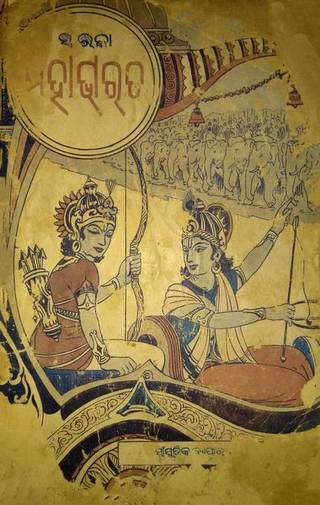

Sarala Das’s 15th-century Odia Mahabharata provides an alternative reading of Vyasa’s canonical text with many surprise elements

In Sarala Das’s Odia version of the Mahabharata, which is the first complete rendition of the epic by a single author in any language other than Sanskrit, Ganga is a wild and tempestuous woman. Born in the world of mortals, she is a dutiful daughter who pines for Shiva. She ends up marrying Shantanu, king of the Kurus, who is a devotee of the lord.

Because Shantanu is not her husband by choice, she finds inventive ways of hurting and humiliating him.

Ganga keeps him starved by cooking tasteless food once in three days, beats him violently at will, tears off his clothes, and destroys his scriptures. Further, she denies him physical pleasure when he seeks it, and forces him to make love on auspicious days when it is forbidden. Later, she kills seven of their children; the eighth one, Bhishma, is saved by the father, and thus Ganga is freed from her marriage. Half-woman, half-river, her wildness as wife is as inexplicable as her gentleness as a daughter before her marriage.

Argumentative women

Like Ganga, many other women in Sarala’s text are open about their desires and have no scruples about expressing these freely. In Vyasa’s Mahabharata, Arjuna becomes attracted to Krishna’s sister Shubhadra and, with the brother’s help, first abducts and then marries her. But in Sarala’s version, it is Shubhadra herself who becomes enamoured of Arjuna; she learns the art of seduction from Padmana’s wife, Mayavati. Thus armed, she seduces Arjuna.

On discovering this premarital affair, Balarama challenges Arjuna to a fight. The latter wins the battle and goes on to marry Shubhadra. As the Sarala scholar B.N. Patnaik says, “The Pandava women were generally manipulative, assertive, argumentative, sometimes noisily so.”

Sarala’s women characters are often much stronger than Vyasa’s, and act independently. This is illustrated in the delightful story about Parvati. Once, early in the morning, Shiva left Kailash astride the bull Nandi and along with his followers. He was supposed to return for lunch. Aparna or Parvati cooked a large, varied spread

for everyone and waited and waited. When it became really late, she sat down to eat, defying the taboo among upper-caste Hindu women that dictated a wife should eat only after the husband has had his fill. When Aparna hears the sound of Shiva’s damru quite late in the day, she is enraged: she throws everything she has cooked into Nandi’s trough. Shiva has to go hungry, but the bull has a feast.

Peasant by birth

In narrating stories like this, the Sarala Mahabharata can be seen as the archetypal non-Brahminical Purana. The poet describes himself as janme krusiakaari, na jaane saastra bidhi — ‘I am a peasant by birth, and do not know the ways of the scriptures’. He also often refers to himself as ‘Shudra muni’ or Shudra sage.

Although bhakti poets took the poetic licence of representing the self as marginal, such self-ascription still points to his subaltern status. Even today, Sarala is often referred to as the Shudra muni in Odisha; the angularities of his poetry are often ascribed to his social position. Marginal characters from non-elite communities, such as Hidimba and her son Ghatotkacha, get more attention in Sarala than they do in Vyasa.

The hardheaded ways in which Sarala deals with sexuality is also in character. Descriptions of sexual acts in his Mahabharata are neither eroticised nor ritualised,as it is in much of medieval Odia literature inspired by the Sanskritic canon.