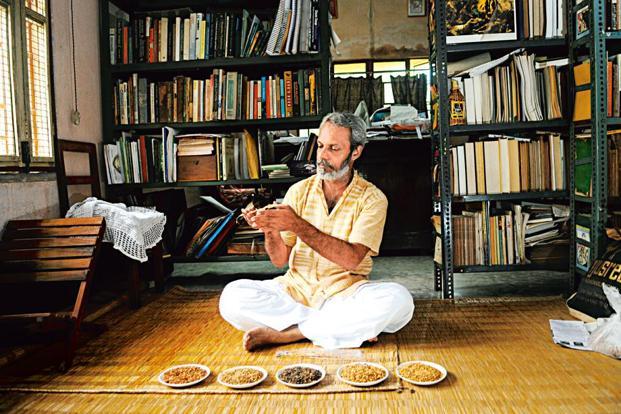

The Sunday morning in July marked the fifth straight day of rain in the fecund foothills of the Niyamgiri range in western Odisha’s Rayagada district. The delayed showers heralded the year’s busiest period for ecologist Debal Deb and his right-hand man Dulal as they prepared Basudha—a 2-acre farm unlike any other in India—for an intricately planned growing season. Wrap your mind around this: Over the coming days, the farm would see the planting of 1,020 indigenous varieties of rice—part of a remarkable effort under way since 1996 to rescue a sliver of India’s genetic diversity from extinction. This wouldn’t just mean planting 1,000 varieties of rice saplings on a plot one-tenth the size of Mumbai’s Oval Maidan, and watching them grow. Maintaining the genetic purity of each of these heirloom varieties, year on year, necessitates an intricate sowing plan crafted by Deb, 53, and his colleagues, so that no two neighbouring varieties flower at the same time, thus guarding against cross-pollination. Deb published his methodology in the Current Science journal in July 2006, after field-testing it for six years. The constant addition of vanishing varieties to Deb’s growing collection—last year, it numbered 960—means the plan needs seasonal redesigning.

Rice—daily sustenance for a majority of Indians—is a grass species, believed to have been domesticated over 7,000 years ago in a broad region extending from the north-eastern Himalayan foothills to southern China and South-East Asia. Over the centuries, human hands selected thousands of different strains, evolved in response to specific ecological niches. The undulating region of western Odisha, called the Jeypore tract, was one of the world’s leading areas of diversification, where a great number of rice varieties, also called landraces, were developed by cultivators—“the unnamed, unknown, and greatly talented scientists of the past,” as Deb describes them. In the 1960s, when Deb was growing up in Kolkata, India was estimated to have over 70,000 such rice landraces. According to a 1991 National Geographic essay, just 20 years later, with scientists and policymakers chasing high yields through aggressively pushed modern, input-intensive hybrids, over 75% of India’s rice production was coming from less than 10 varieties.

Read more at: http://www.livemint.com/Leisure/bmr5i8vBw06RDiNFms2swK/Debal-Deb–The-barefoot-conservator.html?utm_source=copy