It has been a difficult summer for India.

Drought and a searing heat wave have affected an astonishing 330 million people across the country.

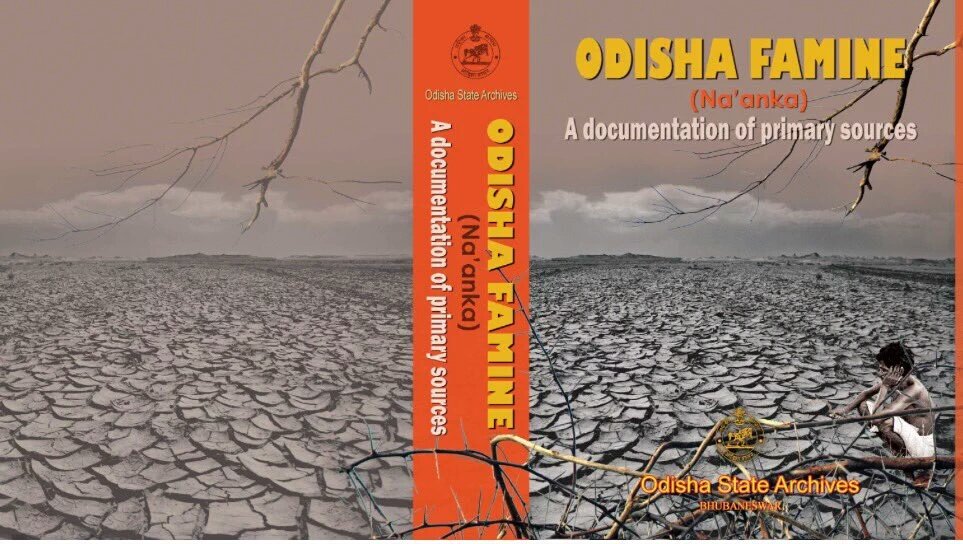

But this summer also marks the 150th anniversary of a far more terrible and catastrophic climatic event: the Odisha famine of 1866.

Hardly anyone today knows about this famine. It elicits little mention in even the densest tomes on Indian history.

There will be few, if any, solemn commemorations. Yet the Orissa famine killed over a million people in eastern India.

n modern-day Orissa state, the worst hit region, one out of every three people perished, a mortality rate far more staggering than that caused by the Irish Potato Famine.

The Orissa famine also became an important turning point in India’s political development, stimulating nationalist discussions on Indian poverty. Faint echoes of these debates still resonate today amid drought-relief efforts.

‘No relief was the best relief’

Famine, while no stranger to the subcontinent, increased in frequency and deadliness with the advent of British colonial rule.

The East India Company helped kill off India’s once-robust textile industries, pushing more and more people into agriculture. This, in turn, made the Indian economy much more dependent on the whims of seasonal monsoons.

One hundred and fifty years ago, as is the case with today’s drought, a weak monsoon appeared as the first ill omen.

“It can, we fear, no longer be concealed that we are on the eve of a period of general scarcity,” announced the Englishman, a Calcutta newspaper, in late 1865.

The Indian and British press carried reports of rising prices, dwindling grain reserves, and the desperation of peasants no longer able to afford rice.

All of this did little to stir the colonial administration into action. In the mid-19th Century, it was common economic wisdom that government intervention in famines was unnecessary and even harmful. The market would restore a proper balance. Any excess deaths, according to Malthusian principles, were nature’s way of responding to overpopulation.

This logic had been used with devastating effect two decades beforehand in Ireland, where the government in Britain had, for the most part, decided that no relief was the best relief.

On a flying visit to Orissa in February 1866, Cecil Beadon, the colonial governor of Bengal (which then included Orissa), staked out a similar position. “Such visitations of providence as these no government can do much either to prevent or alleviate,” he pronounced.

‘Too late, too rotten’

Regulating the skyrocketing grain prices would risk tampering with the natural laws of economics. “If I were to attempt to do this,” the governor said, “I should consider myself no better than a dacoit or thief.” With that, Mr Beadon deserted his emaciated subjects in Orissa and returned to Kolkata (Calcutta) and busied himself with quashing privately funded relief efforts.

In May 1866, it was no longer easy to ignore the mounting catastrophe in Orissa. British administrators in Cuttack found their troops and police officers starving. The remaining inhabitants of Puri were carving out trenches in which to pile the dead. “For miles round you heard their yell for food,” commented one observer.

As more chilling accounts trickled into Calcutta and London, Mr Beadon made a belated attempt to import rice into Orissa. It was, with cruel irony, hindered by an overabundant monsoon and flooding. Relief was too little, too late, too rotten. Orissans paid with their lives for bureaucratic foot-dragging.

For years, a rising generation of western-educated Indians had alleged that British rule was grossly impoverishing India. The Orissa famine served as eye-popping proof of this thesis. It prompted one early nationalist, Dadabhai Naoroji, to begin his lifelong investigations into Indian poverty.

As the famine abated in early 1867, Mr Naoroji sketched out the earliest version of his “drain theory”—the idea that Britain was enriching itself by literally sucking the lifeblood out of India.

“Security of life and property we have better in these times, no doubt,” he conceded. “But the destruction of a million and a half lives in one famine is a strange illustration of the worth of the life and property thus secured.”

Indifferent response

His point was simple. India had enough food supplies to feed the starving – why had the government instead let them die? While Orissans perished in droves in 1866, Mr Naoroji noted that India had actually exported over 200m pounds of rice to Britain. He discovered a similar pattern of mass exportation during other famine years. “Good God,” Mr Naoroji declared, “when will this end?”

It did not end anytime soon. Famines recurred in 1869 and 1874. Between 1876 and 1878, during the Madras famine, anywhere from four to five million people perished after the viceroy, Lord Lytton, adopted a hands-off approach similar to that employed in Ireland and Orissa.

By 1901, Romesh Chunder Dutt, another leading nationalist, enumerated 10 mass famines since the 1860s, setting the total death toll at a whopping 15 million. Indians were now so poor – and the government so indifferent in its response – that, he stated, “every year of drought was a year of famine.”